Debate persists about Oregon farmland loss

Published 10:44 am Thursday, June 5, 2025

Though several controversial land use bills didn’t gain traction in Oregon this year, the discussion over the state’s rate of farmland loss has persisted.

Experts on both sides of the land use debate recently agreed that USDA statistics haven’t accurately captured the rate of farmland conversion to other uses.

However, farmland preservation advocates say the agency’s data still reflects a disturbing trend in Oregon agriculture, while property advocates say the threat of development is greatly exaggerated.

Dave Hunnicutt, president of the Oregon Property Owners Association, recently told lawmakers he rejects the premise that conversion is a growing problem.

“We are not losing farmland in this state,” Hunnicutt said during a legislative hearing on agricultural protections.

Over the past four decades, the 16 million acres zoned for “exclusive farm use” in Oregon has remained virtually unchanged, he said.

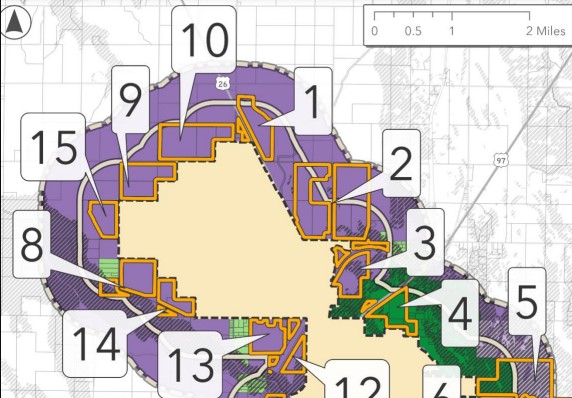

Only about 43,000 acres have been shifted to other zones in that time, largely due to the expansion of “urban growth boundaries” — which haven’t kept up with the state’s population growth, Hunnicutt said.

“At the rate we’re going, if we’re not careful, in 14,884 years we’ll run out of farmland,” he told the Senate Natural Resources Committee.

Jim Johnson, working lands policy director for the 1000 Friends of Oregon nonprofit, countered that stronger agricultural protections are still needed to prevent non-farm uses from undermining the farm industry’s economic viability.

“I will adamantly disagree that we are not losing agricultural land,” Johnson said. “Rural zone changes are not a good measure of farmland loss.”

The dispute over farmland conversion partly centers on the USDA’s finding in the 2022 Census of Agriculture that Oregon lost more than 4% of its agricultural acreage in the preceding five years — a rate exceeding that of four neighboring states.

As farmland preservation advocates acknowledge, though, it’s unlikely that nearly 670,000 acres of Oregon farmland were actually converted to urban or other uses.

“I think it’s important to be skeptical about this data,” said Kelly Howsley-Glover, president of the Association of County Planning Directors.

More than 400,000 acres of that purported farmland loss was determined to have occurred in Wasco County, where Howsley-Glover serves as the community development director.

“I was like, what is going on here? This does not make sense,” she said.

At most, roughly 70,000 acres in the county were converted to solar and wind energy facilities, or dedicated to conservation and recreation uses in that time, Howsley-Glover said.

She told lawmakers the USDA’s estimate was likely influenced by a steep 10% drop in the number of responses to Census of Ag surveys, which the agency tried to “smooth out” with statistical methods.

“Is it a reality that we lost 410,000 acres? No, it is not,” she said. “That is a story the data is telling that is incorrect. There are some flaws in the data.”

The American Farmland Trust, which advocates for farm preservation on a national scale, has called the USDA’s Census of Agriculture figures on farmland loss “misleading,” as they pertain to land management practices rather than what’s actually happened to the “resource base.”

The USDA’s findings reflect the agency’s methodology of counting any property that annually produces $1,000 in agricultural income as a farm, said Hunnicutt of the Oregon Property Owners Association.

The 2022 statistics simply showed that many such properties have stopped generating farm revenues, he said.

“It’s land that was actively being farmed that’s no longer being farmed. It doesn’t mean it’s been converted to anything. It means it’s no longer being farmed,” he said. “What these numbers are telling you is that we are not losing farmland, we are losing farmers.”

Johnson of 1000 Friends of Oregon said it’s true the USDA data has “issues” but defended the utility of the statistics, as they’ve been collected for about 150 years and provide a comparison to other states.

Other information, such as an aerial survey conducted by the Oregon Department of Forestry, corroborates the trend of farmland loss, Johnson said.

Meanwhile, the relatively small decrease of acres zoned for agriculture does not tell the full story of land use changes, he said.

Even within farm zones, fragmentation and “shadow conversion” can subvert the agricultural economy despite properties ostensibly remaining dedicated to farming, said Nelly McAdams, executive of the Oregon Agricultural Trust.

As an example, McAdams pointed to a recent real estate listing for 6,500-square-foot house on 250 acres in Southern Oregon being offered for $8.5 million — an unrealistic price for most farmers hoping to cultivate a property of that size, she said.

“These large homes are white elephants on properties that make them impossible for a producer to purchase,” McAdams said.

Collectively, the construction of luxury homes leads to low-density development that greatly increases the likelihood of conversion to urban uses, she said. “It is kind of a cancer that grows.”

Regardless of the specific rate of farmland loss, the inability of growers to earn money from their land leads to its conversion, said Ryan Krabill, government affairs manager for the Oregon Farm Bureau.

The mounting regulatory burden faced by Oregon farmers contributes to their financial challenges, but it’s a factor over which lawmakers have control, he said.

“When farms can no longer support the families who operate them, that land becomes vulnerable,” Krabill said. “Create an environment where farming by itself becomes profitable again. If you want to protect farmland, we must protect the ability to farm it successfully.”